The Value of Physical Place in Work, Memory, and Life

This week marks our third week “back at work” after quarantine. For nearly four months our team, like most teams, had been among the millions worldwide who suddenly found themselves working from home. While MJM has always had a few remote team members (two on the West coast and one in the Twin Cities) the COVID-19 pandemic forced us to abruptly transition to an all-remote team. We tried to be positive and embrace the new normal, but it presented a fair amount of challenges. I would even say that there was some grieving for what was lost in the daily face-to-face interactions.

I’ve been thinking a lot about that grief, in a time when we are all trying to navigate how to mourn the more grievous loss of life, and I think a big part of the disorientation many are feeling has to do with the loss of the physical spaces we shared. When we go to the places where we work, play, or get coffee, that physical change of place functions as a cue or marker. The erasure of those spaces — and the movement to those spaces — has left us in a trackless sea of mingled social interactions, mostly mediated through our screens.

Finding our place

Physical places help us situate ourselves, both mentally and emotionally. Driving back into your hometown after years away brings a wash of memories. Walking through the halls of your elementary school calls up faces of classmates and teachers. And it’s why “I can still remember where I was when I heard the news” is such a common experience.

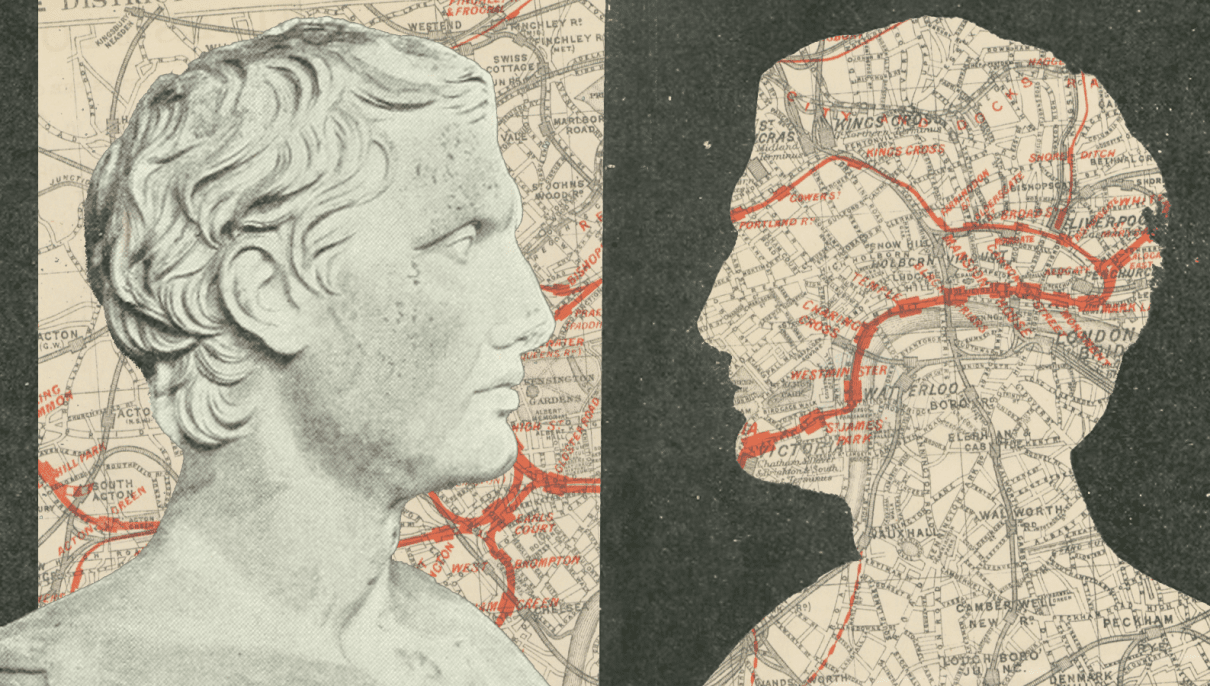

This link between memory and places has long been established. In order to remember their speeches, Roman orators like Cicero would use the “method of loci” to create mental maps of a place — a home or a street of shops — called memory palaces and then mentally associate items to be remembered with each location. To recall the information stored in these memory palaces the speaker would then mentally move through the space, collecting their key points like a shopper in a well-organized grocery store.

In order to remember their speeches, Roman orators like Cicero would use the “method of loci” to create mental maps of a place — a home or a street of shops — called memory palaces and then mentally associate items to be remembered with each location.

Our spatial memory even extends to printed material, and especially content in books. We often remember where on a page we read a certain piece of information (an advantage that is lost when reading in the endless slippery scroll of a digital device.) In a 2014 study done at Norway’s Stavanger University, researchers noticed that subjects were able to more accurately recall the plots of stories they had read in print, when compared with stories read on an electronic device:

“‘When you read on paper you can sense with your fingers a pile of pages on the left growing, and shrinking on the right,’ said [lead researcher Anne Mangen.] ‘You have the tactile sense of progress, in addition to the visual… Perhaps this somehow aids the reader, providing more fixity and solidity to the reader’s sense of unfolding and progress of the text, and hence the story.’”

This may be one reason that readers seem to prefer print books, and often report a deeper emotional connection to the content of a physical book.

Even on a neurological level, our experiences and memories are coded in a way that time and place are deeply intertwined with the content of the memory. Researchers monitoring brain activity during a study that involved having participants play a virtual reality game found that,

“[N]euralrepresentations of the content of the experience had become linked with the spatial and temporal context. Such evidence provides strong evidence for the theory that memory formation and recall involve association of event with context, especially spatial and temporal context. This linkage creates a mutually reinforcing interaction of event and location. We tend to remember both or neither.”

The unifying power of sharing space

If physical spaces shape our memories of the past, they also generate innumerable intangible benefits in our daily lives. Sharing space with others unifies us, almost accidentally, through countless small quotidian interactions. One of the biggest losses we’ve all felt in this season of quarantine and social distancing has been the loss of those incidental interactions that we’d grown accustomed to in our favorite third places1. In his book The Great Good Place, Ray Oldenburg first brought the idea of “third places” to the attention of the wider public:

If physical spaces shape our memories of the past, they also generate innumerable intangible benefits in our daily lives. Sharing space with others unifies us, almost accidentally, through countless small quotidian interactions. One of the biggest losses we’ve all felt in this season of quarantine and social distancing has been the loss of those incidental interactions that we’d grown accustomed to in our favorite third places1. In his book The Great Good Place, Ray Oldenburg first brought the idea of “third places” to the attention of the wider public:

“Most needed are those ‘third places’ which lend a public balance to the increased privatization of home life. Third places are nothing more than informal public gathering places. The phrase ‘third places’ derives from considering our homes to be the ‘first’ places in our lives, and our work places the ‘second.’”

Working from home meant that our “first place” (home) and our “second place” (work) collapsed into one seemingly borderless experience. And now, at a time when our need for some escape from our work and home spaces is most acute, many people are concerned that those third places that formerly offered escape are in danger from both social and economic pressures.

By sharing space before the pandemic, both at work and at home, we unconsciously created a vast bank of shared experiences with members of our community and with our coworkers. At a distance, over Zoom calls and Slack messages, we’re still drawing on that bank of shared experiences, but without opportunities to replenish those connections our mutual connections are being stretched, becoming thin and tenuous. But with cases still on the rise and most traditional third places closing their dine-in spaces, if we’re going to rebuild those connections it’s probably going to have to happen in outdoor public spaces.

Back at work

The MJM space opened back up for business on July 6th. We have gone to great lengths to mitigate the risk of infection, both to ourselves and to clients and vendors. We wears masks when moving around our space, and nixed the communal coffee pot. We also rearranged all our work areas to provide at least 8 feet between each worker. (Brady Holm, our design lead, put together a great post outlining how our process of working together to develop a new office layout was a perfect microcosm for our experiences in remote collaboration.)

As I write this at my appropriately socially-distanced desk back in the MJM space, I believe it’s worth the trouble. Ideas flow quicker in person, and feedback in matters large and small is better. There are daily accidental conversations that connect us and move us forward in our creative work as well as in our friendships — conversations that we never would have scheduled a Zoom call to have, but that came about because we happen to be sharing the same physical space. It’s good to be back at work.

1“The character of a third place is determined most of all by its regular clientele and is marked by a playful mood, which contrasts with people’s more serious involvement in other spheres. Though a radically different kind of setting for a home, the third place is remarkably similar to a good home in the psychological comfort and support that it extends…They are the heart of a community’s social vitality, the grassroots of democracy, but sadly, they constitute a diminishing aspect of the American social landscape.”

“Life without community has produced, for many, a life style consisting mainly of a home-to-work-and-back-again shuttle. Social well-being and psychological health depend upon community. It is no coincidence that the ‘helping professions’ became a major industry in the United States as suburban planning helped destroy local public life and the community support it once lent.” (Ray Oldenburg, quoted by Project for Public Spaces)

Tim is a graphic designer at Matt Jensen Marketing.